Emulator-Backed Remakes

Introduction

“Back in my day, games were better. They were more fun because gameplay was more important than graphics.”

–Gamers born in any given decade

No matter what “back then” is for you, you probably identify with this opinion to some degree. For me it was the mid-80s to mid-90s, when I enjoyed countless hours of Sir Fred, Atic Atac, Airborne Ranger, Monkey Island, Twilight: 2000, Stunts, Gunship 2000, Twinsen’s Adventure, Dark Sun, Challenge for Ancient Empires, the X-Wing series, and so many others.

Sometimes nostalgia attacks and you want to play one of these games again. You have several options.

Play a remastered version. Some games are so awesome and have such a loyal fan base that an official “new edition” comes out. This is exactly the same game, but with modern art. A great example is the awesome Monkey Island Special Edition.

This is the ideal scenario. Unfortunately, very few games are remastered due to cost, the original source being lost, or even lack of interest in the case of relatively obscure games.

A related category is games that have been open sourced, such as Id’s first person shooters. There are some projects to produce new art packs for these games, but these are rare and not many games are open sourced to begin with.

Play a remake. Some games are so awesome and have a such loyal fan base that someone decides to rewrite the game from scratch, usually without any support from the original authors. When you can find a good remake, you get almost the original game, but with modern art.

This is a good alternative, but again, very few games have remakes. This is because remakes are usually fan made, and the task is enormously difficult - it is as difficult as making a game from scratch, with the additional difficulty of trying to replicate the original gameplay as closely as possible. The only way to reach a really high level of accuracy is to actually disassemble the original code and replicate the logic.

Use an emulator. There’s always DOSBox, and specific solutions for certain games, such as ScummVM. This works, but let’s be honest, most games haven’t aged well from an art perspective. You do play exactly the original games, though.

Summary

If there’s a remastered version of the game you want to play, great! But for the vast majority of games which don’t have one, you are left with two options: use an emulator (widely available, perfect gameplay, outdated art) or hope someone makes a remake (relatively rare, imperfect gameplay, modern art).

A new approach

But what if we could run the original binary game code unmodified, just with better art?

Suppose you have a game running in an emulator. You don’t have the source code, but you can be sure there is a “draw a sprite” method buried somewhere in the binary code. Or a “write a character” method. Or a “play a sound effect” method. Or a “render a polygon” method.

What if you could use a debugger/disassembler integrated with the emulator to discover the entry points to these methods? What if you could figure out what registers contain what parameters, or their order in the stack?

What if you could instruct the emulator to call an arbitrary C++ method whenever these entry points were about to be executed, extract the state of the registers at that point, and execute your own sprite drawing code? Or TrueType font rendering code? Or MP3 playing code? Or a few OpenGL calls?

If you managed to replace all these methods with C++ implementations, you’d end up with a game that follows the exact logic of the original, but looks modern. An emulator-backed remake with perfectly accurate gameplay that you can build incrementally and with just a very superficial understanding of the disassembly.

I did some research and this seems to be an original idea. Why hasn’t anyone tired this before?

Could this possibly work?

A proof of concept

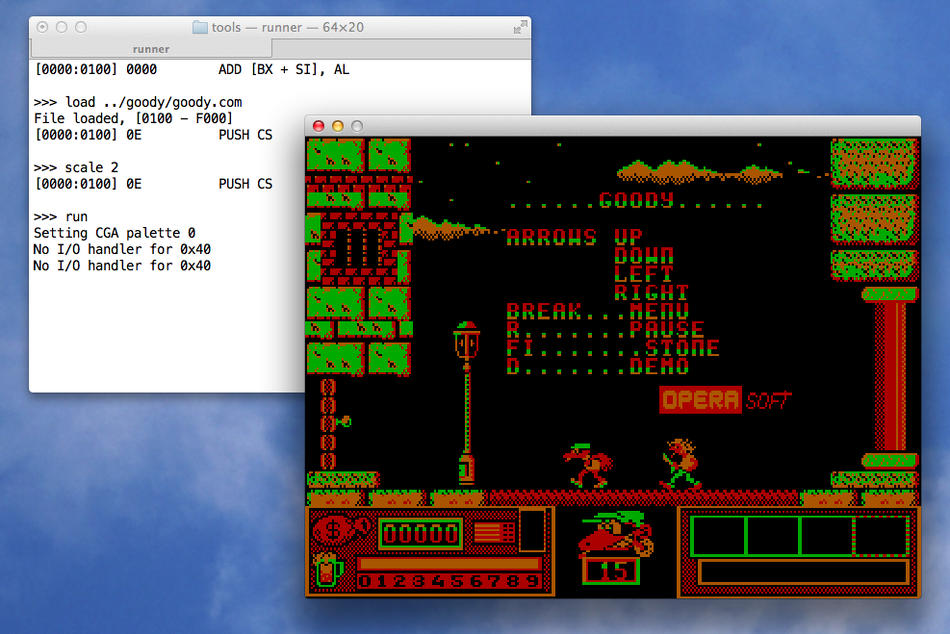

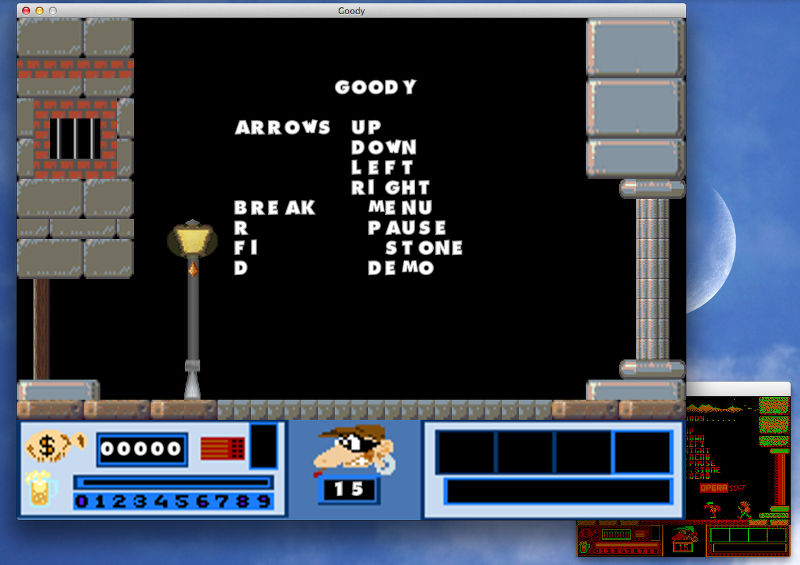

I decided to put this crazy idea to the test. I wrote an 8086 + CGA emulator with only 44 opcodes implemented, which is barely enough to run the intro screen of Goody:

I wrote two tools - a disassembler and a runner that lets you execute the code step by step, set breakpoints and so on, with an interface similar to gdb.

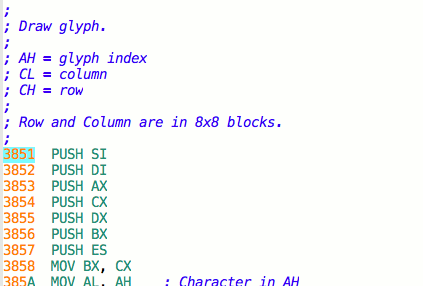

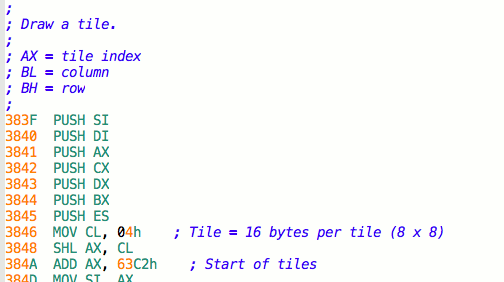

Short of disassembling the whole thing, how can you find interesting functions? I used a variety of techniques - setting breakpoints and inspecting the registers, running the code a handful of instructions at a time, randomizing the contents of the simulated video RAM to see what was being drawn, patching the code to skip some calls to see what stopped working - and some examination of the disassembled code to add comments as I was making sense of it.

Using these techniques I was able to find several interesting “functions”:

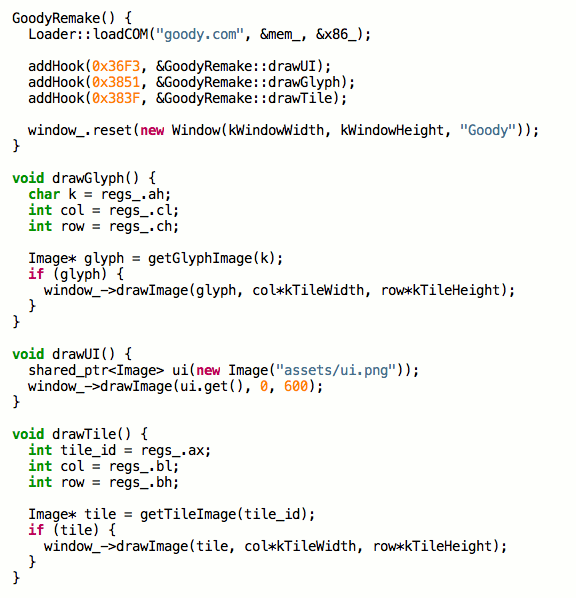

I added some C++ hooks to do some custom drawing in a separate window:

I hacked together some placeholder art, crossed my fingers, and…

…lo and behold, I got a “remake” going! Note the “old” window running side by side with the “new” window; this is not a static image, but new art driven by the original X86 code!

See for yourself

The whole demo (the x86 emulator / disassembler / debugger, the Goody hooks, and the placeholder art) is available at GitHub. It works in Linux and Mac; it requires SDL2 and a C++0x compiler.

The source code is licensed under the Whatever/Credit license: you may do whatever you want with the code; if you make something cool, credit is appreciated. By the way, the code isn’t even alpha quality - it’s “proof of concept / runs in my machine” quality.

The repository includes the original game (goody.com) - I got the unofficial blessing from Gonzo Suárez, one of the original authors, to distribute it, and it’s also easily available in any abandonware site; but I’ll remove from the distribution if there’s any objection.

I hacked together the art using my terrible Gimp skills and some Public Domain and Creative Commons assets from OpenGameArt: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. If an artist reading this wishes to donate original art for this demo, I’d be very thankful :)

Answers to expected questions

Q: You do know there’s a perfectly good Goody remake, right?

A: Yes. But I choose Goody as a proof of concept because it’s the game I liked the most from the CGA era, because it’s self-contained in a COM file meaning no EXE loader would be needed, and because it was clearly tile-based so I guessed it would be relatively straightforward to deal with.

Q: Why didn’t you use any of the available x86 emulators, or even DOSBox?

A: Because writing a x86 emulator is a fun challenge. Beyond the proof of concept phase, I fully intend to repurpose DOSBox for this.

Closing Thoughts

Does it scale?

Can these techniques be applied to more complex games? I don’t see why not. You can always start from DOSBox and substitute, say, the audio. That would be the start of a partial remake.

A different question is where to draw the line - at what level of abstraction to add the hooks. In a sense, you could say DOSBox hooks at the lowest possible level - drawing individual pixels. My proof of concept hooks at the “draw a tile” and “draw a glyph” level. But take fonts, for example. Drawing glyph by glyph is OK for things like the money and lives counters, but we can do better for the instructions text in the main screen - hook at the “draw a string” level instead and use FreeType, to get a proportional font with nice kerning.

A similar reasoning applies for software-rendered 3D games like X-Wing or Stunts. It should be possible to hook the “render a triangle” function, in which case you’d get very low poly models rendered by your GPU, or hook the “render a model” function and use new 3D models. Or consider the original Wing Commander, which didn’t even use 3D models - instead of just using higher-resolution spaceship bitmaps, you could actually render 3D spaceships.

Another example is sound. You could intercept the programmable timer and speaker I/O ports and generate the corresponding waveform on the fly (this is presumably what DOSBox does), or you could hook the “play a sound effect” function and play some MP3 instead.

What about frame rates? The “Goody dying” animation is two frames and lasts for around a second. Even with nice assets, the animation would still look choppy. I think the solution for problems of this kind is to be smarter about the way the state is rendered - ideally, you could write a completely new renderer based on the state of the game as read from memory without needing to hook any drawing method directly.

Applicability beyond games

This idea could even be applied beyond games. One of the reasons very old software is used in some installations is because there’s so much business logic details added throughout the years, it would be impossible/impractical to rewrite some systems from scratch. But using these techniques, it could be possible to run the logic unmodified and replace the input/output/database code with something modern.

Legality

While this is not legal advice because I’m not a lawyer, I can’t think of any reason this technique itself could be illegal, as long as the “remake” doesn’t bundle the original binary of the game (except if the game itself is freely distributable, of course).

Art is trickier. Again, a remake shouldn’t include any of the original art; artists would need to remake MP3 of it from scratch. But even then, I’m not sure whether making, say, 3D models of an X-Wing or a picture of Darth Vader is OK. Maybe it could be considered fan art?

Further reading

If you’re into reverse engineering, old games, or both, check out Fabien Sanglard’s website.

Summary

This proof of concept validates the idea; it’s not just a crazy idea after all. Remakes can be done by hooking modern rendering/sound/networking code into an emulator/VM that runs the original game.

Will this revolutionize the way remakes are made? I certainly hope so! I’d love to play the games of the past with a modern look and the original gameplay :)